For me, one of the most exciting features of J. Michael Straczynski’s (JMS) run on the Amazing Spider-Man (2001-2007) was his decision to give Peter Parker a stable job. The choice of occupation was a perfect fit, in my opinion, and illustrated JMS’s understanding of the best of the character. At his core and his best, Peter Parker is defined by the drive to do good, to set things right, to see responsibility and maturity triumph in an insane world that rewards the maniacal and offers riches and multiple escape routes to the careless and thoughtless who only think about “Number 1.”

Peter’s life, after the death of Uncle Ben, has been about troping blind grandstanding and braggadocio while always trying to make a positive impact on his world (Spidey is the quipy confident; Peter the worrywart) whether as penance or simply the only way he can live with himself and his social realities. Peter’s “life world” has always made him an excellent fit for the teaching profession, so JMS made him a substitute science teacher. Brilliant!

Shortly after JMS left Spidey in 2007, I stopped reading. The events and happenings since Staczynski’s efforts to re-establish the essence and ethos of the character seem shallow and false, what with the shirking of responsibility, odd choices, and the deal with Mephisto, Marvel’s top yet-still-third tier Satan analogue who hasn’t done much since toying with the Thing and the Beyonder in Marvel Secret Wars II.

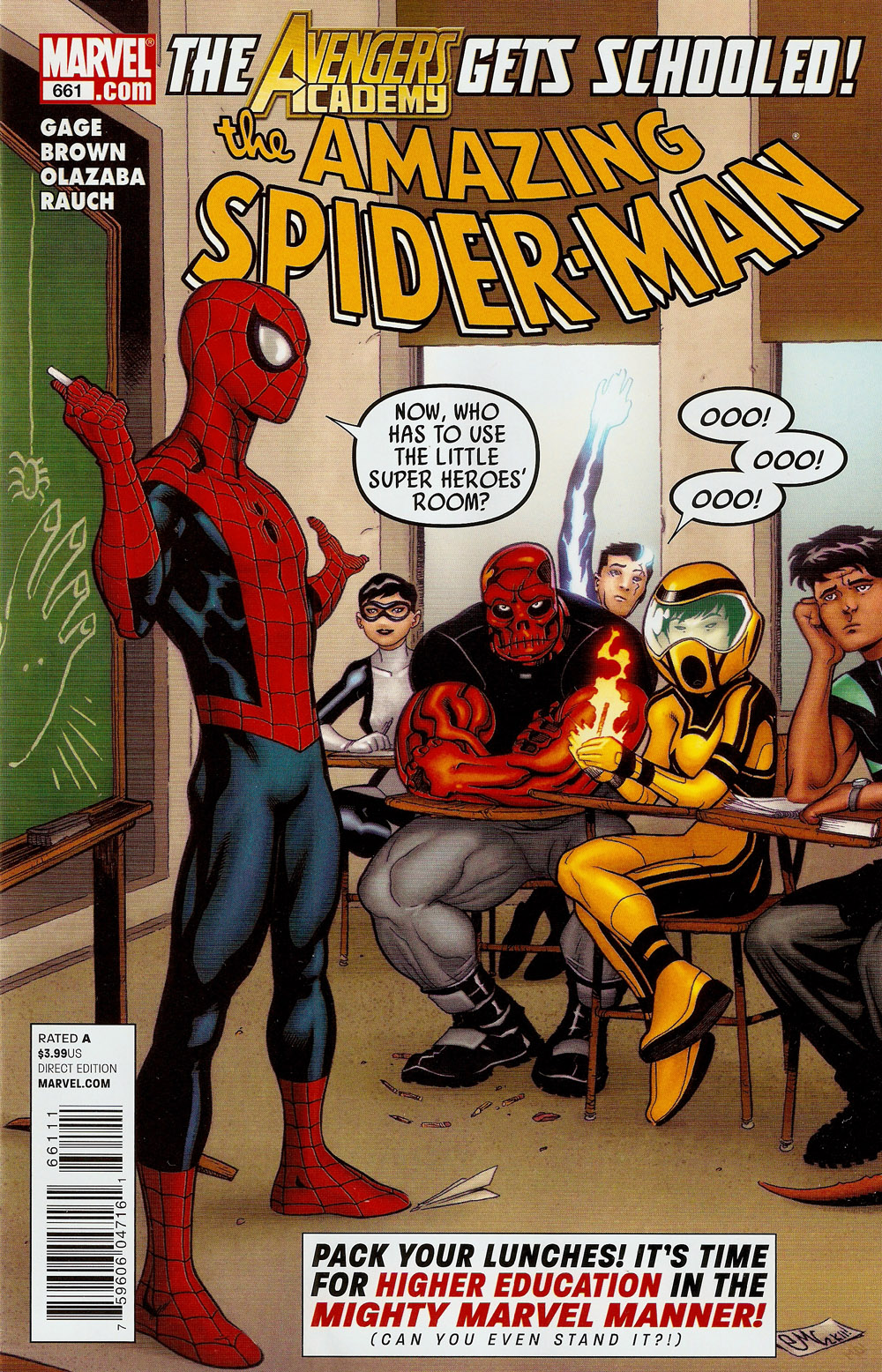

So, imagine my joy when I saw Avengers Academy guest-starring in the Amazing Spider-Man #661, complete with a cover image of Spider-Man at the chalkboard in front of the group of teen heroes (OK, the posture doesn’t represent the best of a constructivist classroom, but we can’t expect a cover artist to me 100% savvy in the was of contemporary pedagogy, can we?).

The issue finds Spidey’s new team, the Freedom Foundation, very busy with an overgrown ape and getting an assist from Hank Pym (Giant Man), the headmaster of Avengers Academy, who informs the heroes that his “core faculty” is busy tomorrow, so he needs a substitute. Peter is quick to volunteer, though Giant Man had the Thing in mind.

“Now hold on just one flippin’ second!” Peter retorts. “…I have a teacher’s license! I taught kids for a living!” he says with pride. So, he convinces Pym to let him substitute for a day.

While it is a joy for me to see Peter back in the classroom for reasons mentioned above, and it is nice to see writer Christos Gage acknowledging JMS’s contributions to the Spider-Man mythos, it is particularly interesting to see how the creative team handle the phenomenon of teaching. How intriguing is it? Enough so that I just used “particularly” as an adjective describing “interesting” even though I had to split the verb phrase to do it.

Media representations of teachers and teaching have been noticed by teacher educators. Catherine Carter, the English methods professor at my undergraduate alma mater, Western Carolina University, recently published an article on the topic in English Education in which she pointed out how misleading, if not dangerous, media messages about teaching can be for those young people considering the profession as well as for those already in the profession, who must not only gauge themselves against the impossible in reality, but also in what ad campaigns and Hollywood have construed as effective teaching. One of my doctoral mentors from the University of Virginia, Margo Figgins, has co-created a multimedia piece of scholarship exploring representations of teaching in film and warned of similar worries.

So, what does AMS #661 suggest about teaching, and is it healthy for the profession? What utility might this issue have for practicing teachers, teacher educators, pre-service teacher candidates and teacher-student relationships in general? Let us consider what the comic offers.

I have mentioned the cover, which might as well be a still from Welcome Back, Kotter or Head of the Class. The teacher is at the front of the room, holding chalk and referencing his scribble, while the class is scrunched together in a set of uncomfortable wooden desks in a sparse room. We have representations of the eager beaver, the silent but attentive, the bored jock, the bored every guy, and the jokester among the students. The eager beaver character is most eager to go to the restroom, though, as Spidey makes a silly mistake in asking the entire class who needs to use the “little super heroes room.” Where’s the hall pass? The toilet seat? I know you’re a sub, Peter, but shouldn’t you have a system in place? ;)

The cover image represents a rather media-saturated image of the student-teacher dynamic, complete with stereotypical modes of discourse, seating arrangements, students, environment, and rookie mistakes.

Inside the comic, Peter’s interaction with Hank Pym seems more about proving his worth than about a love of teaching, more about wanting to be acknowledged as an important member of his social groups than about making a difference. He is proud to have been a teacher and to have earned a license! So, when Pym says that “changes everything,” Spidey is happy, only to learn that Giant Man thinks he’ll be a good sub not only because of his credentials, but because of the mistakes he made as a teen hero too. Ever the Charlie Brown in spandex, the Spider-Man. He can’t win for losing.

His penchant for earning backhanded praise spins directly and immediately into a surely correlated aspect of his neuroses: self-doubt. A cut-away reveals Peter walking with friend Carlie. Hat is he most worried about?:

Peter: I mess up a lot, Carlie [….] It’s not a big deal…You learn from your

mistakes.

Peter: But these are at-risk kids. I could ruin their whole lives.

Carlie: Or save them.

The teacher as savior myth is clearly at work, or at least the possibility of it. Peter Parker as great white savior of kids on the fringe might bring to mind any number of films where it seems a naive white teacher gets students to learn math or literature after earning their trust and delivering a corny rap. The idea comes from Carlie, not the experienced Peter, so who is to know how Peter reacts to her attempt to comfort him? The writer gives us none of his reaction, instead cutting to the beginning of class the next day.

It should also be noted that this myth of the savior, especially the “great white savior” is complicated a bit since it is Spider-Man, not Peter Parker, who teaches the class. No one knows Spidey’s alter-ego, so he could be of any race or origin, though his students do seem to know his (Spider-Man’s, not Peter’s) history as a costumed presence in New York City.

While the “teacher as savior” utterance might offer means of exploring other instances of the concept in media and/or help pre-service teachers question their motivations and the realities of transformational pedagogy, so too can Peter’s worry inform our understanding of teaching, specifically who is worthy or qualified to teach.

Peter is worried that his mistakes make him a liability, that his proclivity for messing up means he has nothing to offer students, or, at worst, suggests he could ruin them. Teacher as “saint” is reflected in his reservations. There seems to be in popular thought the idea that a teacher needs to hide his or her past and be the perfect human being. I remember the gall my first principal felt I had for admitting to my students that “I had made mistakes before” when they asked me if I had ever smoked marijuana. We all know of instances of schools implementing policy restricting teachers from making their presidential preferences known to students, and a recent bill in Tennessee will ban homosexual teachers or those who want to explore social issues related to homosexuality from using the word “gay” in school grounds, the assumption from the bill’s sponsors most-likely being that “gay” somehow equates to “immoral” or ‘unchristian.”

I believe Peter’s brief interaction with Carlie offers much to debate and discuss for teachers and students and especially for teacher educators and their pre-service students. Who is best to teach?: The sinner or the saint? The one with troubled life experiences or the one with an easy life to date Are these binaries even possible? Why do we decide to become teachers in the first place? What drives us? How deep do the rivers of our motivations run? Do they go deeper than what the films like Dangerous Minds or Freedom Writers tell us about teaching? If not, where to go from there?

What’s more, what about our lives can damage kids? This is the other major myth to evolve from the exchange: tainted as one who can only taint. The “sinner” as negative destructive influence, as the one who can never be washed clean and can only pass along his natural depravity. The same questions as mentioned above still seem relevant. But, how often in the media is our teacher construct considered tainted, except by convention? Others taint the media-constructed teacher, not his or her life experiences. The teacher is the “rebel in the right” whereas the “establishment” only sees the troublesome rebel who must be removed. Apparently, principals ad parents prefer that someone more like the saint put all those pages back in the Anthology of American Literature. Robin Williams should keep on walking.

Despite the traditional desk layout and teacher-student proximics apparent at the beginning of Spidey’s class, the subject is on the more abstract side of the Bloom and Marzano scales. Spidey uses Socratic techniques to get the students to consider super-hero ethics.

SM: So let’s say you’e in school in your civilian identity. Some jock gives you a

wedgy in front of a bunch of hot girls and calls you “egghead”…What do

you do?

SM: You’re on a date. A bad guy robs a bank nearby…

As the students answer, another popular myth from film and television emerges: the child as genius; or, more aptly put, the “everychild” as smarter than the “everyadult.” They offer answers that seem beyond Spidey’s paradigmatic understanding of the super-hero dynamic, then they tell him how the hip new young people do it. Duh! The in-class portion of the lesson ends when Spidey is unable to adequately answer a question from a student who inquires as to what is the best use of one’s super-powers, fighting villains or helping fight disease through capitalizing on one’s abilities.

Meet the Amazing, Out-Of-Touch Spider-Man: Spectacular fogie.

As I have said before in an essay exploring concepts of education, multiculturalism, and acculturation in the X-Men comics, especially in the dynamic of Xavier’s School for Gifted Youngsters, any representation of schooling and teaching, whether it be from a Norman Rockwell painting, a film, or an advertising campaign, can help us inform our own notions of pedagogy and explore what messages are being marketed to us about teaching, teachers, and students – if we acknowledge the fact and directly, overtly, critically examine the images put before us.

What is especially interesting in comics – super-hero comics, anyway – is that overt pedagogical instances often morph into vocational education. Comics aren’t the only form of media playing with vocational education these days. Hogwarts is a school for wizards, after all. The students in the film Hero High mimic the X-Men in that they are in school to learn how to use their powers for good. But, comics offer multiple instances of not only vocational education, but on-the-job training. Pedagogy of place and pedagogy of experience often supersede the classroom dynamic. Dewey might very well love how young people learn in comics, if their field trips didn’t put them in danger of dying.

Spidey takes Avengers Academy on patrol, and soon enough the teens stop a robbery. Spidey evaluates their performance and offers critique. Students offer counter-evidence of said critique. A dialogic is created, and why shouldn’t it be? It’s an authentic instance and an authentic learning environment. And in such situations, experience matters. Spidey is able to save the children from the doubts and fears the “surprise villain” Psycho Man has instilled in them. Spider-Man fights those feelings too, along with more doubt, but overcomes them because he knows they come from external stimuli, not really from within. The issue ends on a cliffhanger, with Psycho Man turning the teens against the teacher using not fear or doubt, but by mind-controlling them through hate. It appears the teacher is about to become the student, the boys and girls will be the mothers and fathers of the man, who will die an old fogie death and make room for the new breed and culture.

One shouldn’t fault a comic book for having a comic book ending, of course. But it is interesting to examine the reasons behind why the in-class portion of the lesson was a struggle while the kids seemed to thrive in a situation that was real-life, in real-time, and concretely situated. Does this suggest a limit to the benefits of abstract, high-level thinking? A sort of proof of what Milton regaled as the benefits of active virtue? If students can’t test their philosophical opinions, what good are they? Mustn’t education have to come out from the desk, but also out from the classroom? Is a more vocational education experience better than one that is strictly academic? How does a constructivist approach fit into either or both dynamics, and how, if possible, can we blend pedagogies of experience with school building-centric curricula?

Or are we simply reading too much into yet another media construction of the student-teacher dynamic? Are we being influenced by more false truths about teaching in the final scene of the Amazing Spider-Man #661?

So, what does AMS #661 suggest about teaching, and is it healthy for the profession? What utility might this issue have for practicing teachers, teacher educators, pre-service teacher candidates and teacher-student relationships in general? It offers a unique, multimodal way “in” to discussing matters of the profession and perceptions of it. The issue is situated in the media but also strangely detached from dominant media discourses in the way that millions might see a film version of a comic, but only tens of thousands might read the source material. The comic book therefore is a media construct and may be subject to all that entails, but it might also benefit (or suffer) from the distancing effect of distribution and readership/ viewership, the insider on the outside. Teachers and students at the k-12 level and teacher educators and their pre-service teachers can mine that dynamic to get at the others regarding the phenomenon of contemporary teaching.

Shortly after JMS left Spidey in 2007, I stopped reading. The events and happenings since Staczynski’s efforts to re-establish the essence and ethos of the character seem shallow and false, what with the shirking of responsibility, odd choices, and the deal with Mephisto, Marvel’s top yet-still-third tier Satan analogue who hasn’t done much since toying with the Thing and the Beyonder in Marvel Secret Wars II.

So, imagine my joy when I saw Avengers Academy guest-starring in the Amazing Spider-Man #661, complete with a cover image of Spider-Man at the chalkboard in front of the group of teen heroes (OK, the posture doesn’t represent the best of a constructivist classroom, but we can’t expect a cover artist to me 100% savvy in the was of contemporary pedagogy, can we?).

The issue finds Spidey’s new team, the Freedom Foundation, very busy with an overgrown ape and getting an assist from Hank Pym (Giant Man), the headmaster of Avengers Academy, who informs the heroes that his “core faculty” is busy tomorrow, so he needs a substitute. Peter is quick to volunteer, though Giant Man had the Thing in mind.

“Now hold on just one flippin’ second!” Peter retorts. “…I have a teacher’s license! I taught kids for a living!” he says with pride. So, he convinces Pym to let him substitute for a day.

While it is a joy for me to see Peter back in the classroom for reasons mentioned above, and it is nice to see writer Christos Gage acknowledging JMS’s contributions to the Spider-Man mythos, it is particularly interesting to see how the creative team handle the phenomenon of teaching. How intriguing is it? Enough so that I just used “particularly” as an adjective describing “interesting” even though I had to split the verb phrase to do it.

Media representations of teachers and teaching have been noticed by teacher educators. Catherine Carter, the English methods professor at my undergraduate alma mater, Western Carolina University, recently published an article on the topic in English Education in which she pointed out how misleading, if not dangerous, media messages about teaching can be for those young people considering the profession as well as for those already in the profession, who must not only gauge themselves against the impossible in reality, but also in what ad campaigns and Hollywood have construed as effective teaching. One of my doctoral mentors from the University of Virginia, Margo Figgins, has co-created a multimedia piece of scholarship exploring representations of teaching in film and warned of similar worries.

So, what does AMS #661 suggest about teaching, and is it healthy for the profession? What utility might this issue have for practicing teachers, teacher educators, pre-service teacher candidates and teacher-student relationships in general? Let us consider what the comic offers.

I have mentioned the cover, which might as well be a still from Welcome Back, Kotter or Head of the Class. The teacher is at the front of the room, holding chalk and referencing his scribble, while the class is scrunched together in a set of uncomfortable wooden desks in a sparse room. We have representations of the eager beaver, the silent but attentive, the bored jock, the bored every guy, and the jokester among the students. The eager beaver character is most eager to go to the restroom, though, as Spidey makes a silly mistake in asking the entire class who needs to use the “little super heroes room.” Where’s the hall pass? The toilet seat? I know you’re a sub, Peter, but shouldn’t you have a system in place? ;)

The cover image represents a rather media-saturated image of the student-teacher dynamic, complete with stereotypical modes of discourse, seating arrangements, students, environment, and rookie mistakes.

Inside the comic, Peter’s interaction with Hank Pym seems more about proving his worth than about a love of teaching, more about wanting to be acknowledged as an important member of his social groups than about making a difference. He is proud to have been a teacher and to have earned a license! So, when Pym says that “changes everything,” Spidey is happy, only to learn that Giant Man thinks he’ll be a good sub not only because of his credentials, but because of the mistakes he made as a teen hero too. Ever the Charlie Brown in spandex, the Spider-Man. He can’t win for losing.

His penchant for earning backhanded praise spins directly and immediately into a surely correlated aspect of his neuroses: self-doubt. A cut-away reveals Peter walking with friend Carlie. Hat is he most worried about?:

Peter: I mess up a lot, Carlie [….] It’s not a big deal…You learn from your

mistakes.

Peter: But these are at-risk kids. I could ruin their whole lives.

Carlie: Or save them.

The teacher as savior myth is clearly at work, or at least the possibility of it. Peter Parker as great white savior of kids on the fringe might bring to mind any number of films where it seems a naive white teacher gets students to learn math or literature after earning their trust and delivering a corny rap. The idea comes from Carlie, not the experienced Peter, so who is to know how Peter reacts to her attempt to comfort him? The writer gives us none of his reaction, instead cutting to the beginning of class the next day.

It should also be noted that this myth of the savior, especially the “great white savior” is complicated a bit since it is Spider-Man, not Peter Parker, who teaches the class. No one knows Spidey’s alter-ego, so he could be of any race or origin, though his students do seem to know his (Spider-Man’s, not Peter’s) history as a costumed presence in New York City.

While the “teacher as savior” utterance might offer means of exploring other instances of the concept in media and/or help pre-service teachers question their motivations and the realities of transformational pedagogy, so too can Peter’s worry inform our understanding of teaching, specifically who is worthy or qualified to teach.

Peter is worried that his mistakes make him a liability, that his proclivity for messing up means he has nothing to offer students, or, at worst, suggests he could ruin them. Teacher as “saint” is reflected in his reservations. There seems to be in popular thought the idea that a teacher needs to hide his or her past and be the perfect human being. I remember the gall my first principal felt I had for admitting to my students that “I had made mistakes before” when they asked me if I had ever smoked marijuana. We all know of instances of schools implementing policy restricting teachers from making their presidential preferences known to students, and a recent bill in Tennessee will ban homosexual teachers or those who want to explore social issues related to homosexuality from using the word “gay” in school grounds, the assumption from the bill’s sponsors most-likely being that “gay” somehow equates to “immoral” or ‘unchristian.”

I believe Peter’s brief interaction with Carlie offers much to debate and discuss for teachers and students and especially for teacher educators and their pre-service students. Who is best to teach?: The sinner or the saint? The one with troubled life experiences or the one with an easy life to date Are these binaries even possible? Why do we decide to become teachers in the first place? What drives us? How deep do the rivers of our motivations run? Do they go deeper than what the films like Dangerous Minds or Freedom Writers tell us about teaching? If not, where to go from there?

What’s more, what about our lives can damage kids? This is the other major myth to evolve from the exchange: tainted as one who can only taint. The “sinner” as negative destructive influence, as the one who can never be washed clean and can only pass along his natural depravity. The same questions as mentioned above still seem relevant. But, how often in the media is our teacher construct considered tainted, except by convention? Others taint the media-constructed teacher, not his or her life experiences. The teacher is the “rebel in the right” whereas the “establishment” only sees the troublesome rebel who must be removed. Apparently, principals ad parents prefer that someone more like the saint put all those pages back in the Anthology of American Literature. Robin Williams should keep on walking.

Despite the traditional desk layout and teacher-student proximics apparent at the beginning of Spidey’s class, the subject is on the more abstract side of the Bloom and Marzano scales. Spidey uses Socratic techniques to get the students to consider super-hero ethics.

SM: So let’s say you’e in school in your civilian identity. Some jock gives you a

wedgy in front of a bunch of hot girls and calls you “egghead”…What do

you do?

SM: You’re on a date. A bad guy robs a bank nearby…

As the students answer, another popular myth from film and television emerges: the child as genius; or, more aptly put, the “everychild” as smarter than the “everyadult.” They offer answers that seem beyond Spidey’s paradigmatic understanding of the super-hero dynamic, then they tell him how the hip new young people do it. Duh! The in-class portion of the lesson ends when Spidey is unable to adequately answer a question from a student who inquires as to what is the best use of one’s super-powers, fighting villains or helping fight disease through capitalizing on one’s abilities.

Meet the Amazing, Out-Of-Touch Spider-Man: Spectacular fogie.

As I have said before in an essay exploring concepts of education, multiculturalism, and acculturation in the X-Men comics, especially in the dynamic of Xavier’s School for Gifted Youngsters, any representation of schooling and teaching, whether it be from a Norman Rockwell painting, a film, or an advertising campaign, can help us inform our own notions of pedagogy and explore what messages are being marketed to us about teaching, teachers, and students – if we acknowledge the fact and directly, overtly, critically examine the images put before us.

What is especially interesting in comics – super-hero comics, anyway – is that overt pedagogical instances often morph into vocational education. Comics aren’t the only form of media playing with vocational education these days. Hogwarts is a school for wizards, after all. The students in the film Hero High mimic the X-Men in that they are in school to learn how to use their powers for good. But, comics offer multiple instances of not only vocational education, but on-the-job training. Pedagogy of place and pedagogy of experience often supersede the classroom dynamic. Dewey might very well love how young people learn in comics, if their field trips didn’t put them in danger of dying.

Spidey takes Avengers Academy on patrol, and soon enough the teens stop a robbery. Spidey evaluates their performance and offers critique. Students offer counter-evidence of said critique. A dialogic is created, and why shouldn’t it be? It’s an authentic instance and an authentic learning environment. And in such situations, experience matters. Spidey is able to save the children from the doubts and fears the “surprise villain” Psycho Man has instilled in them. Spider-Man fights those feelings too, along with more doubt, but overcomes them because he knows they come from external stimuli, not really from within. The issue ends on a cliffhanger, with Psycho Man turning the teens against the teacher using not fear or doubt, but by mind-controlling them through hate. It appears the teacher is about to become the student, the boys and girls will be the mothers and fathers of the man, who will die an old fogie death and make room for the new breed and culture.

One shouldn’t fault a comic book for having a comic book ending, of course. But it is interesting to examine the reasons behind why the in-class portion of the lesson was a struggle while the kids seemed to thrive in a situation that was real-life, in real-time, and concretely situated. Does this suggest a limit to the benefits of abstract, high-level thinking? A sort of proof of what Milton regaled as the benefits of active virtue? If students can’t test their philosophical opinions, what good are they? Mustn’t education have to come out from the desk, but also out from the classroom? Is a more vocational education experience better than one that is strictly academic? How does a constructivist approach fit into either or both dynamics, and how, if possible, can we blend pedagogies of experience with school building-centric curricula?

Or are we simply reading too much into yet another media construction of the student-teacher dynamic? Are we being influenced by more false truths about teaching in the final scene of the Amazing Spider-Man #661?

So, what does AMS #661 suggest about teaching, and is it healthy for the profession? What utility might this issue have for practicing teachers, teacher educators, pre-service teacher candidates and teacher-student relationships in general? It offers a unique, multimodal way “in” to discussing matters of the profession and perceptions of it. The issue is situated in the media but also strangely detached from dominant media discourses in the way that millions might see a film version of a comic, but only tens of thousands might read the source material. The comic book therefore is a media construct and may be subject to all that entails, but it might also benefit (or suffer) from the distancing effect of distribution and readership/ viewership, the insider on the outside. Teachers and students at the k-12 level and teacher educators and their pre-service teachers can mine that dynamic to get at the others regarding the phenomenon of contemporary teaching.

No comments:

Post a Comment